Sitting in a clinic in Northern Malawi, Dr Peter Harrington—a Wexford-based GP usually practicing in the Palms GP Surgery, Gorey, but also leading an overseas health partnership in Malawi funded by the HSE—remembers witnessing a 12-year-old boy struggling to walk from the waiting room into the clinic room.

“He was swollen and short of bre ath and had nobody to accompany him. The clinical officer looked at his notes briefly and handed him a prescription for a fluid tablet,” Harrington remembers. “It was already too late.”

ath and had nobody to accompany him. The clinical officer looked at his notes briefly and handed him a prescription for a fluid tablet,” Harrington remembers. “It was already too late.”

The diagnosis was heart failure due to rheumatic heart disease – a condition that is a thing of the past in Ireland, but still all too common in developing countries.

In most parts of the world, the fact that an untreated sore throat can lead to heart failure and death at a young age has thankfully been forgotten. Common in Ireland until the 1960’s, rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is a complication of infection with the group A streptococcal bacteria The streptococcal throat infection that often precedes RHD is now effectively managed with good access to primary care and improved living conditions. Early treatment can make the vital difference between life and death. However, despite this, in lower income countries, an estimated 33 million people suffer from this condition and 330,000 people die from it each year, mostly in their 20’s and 30’s.

It has also been mostly forgotten that it was an Irish physician working in West Cork in 1940s Ireland, who made a historical leap in demonstrating the effectiveness of penicillin to curtail the onset of RHD. Working out of his small GP practice in Skibereen, Dr PJ Burke, writing in The Lancet in 1947, first documented in a controlled study the effects of oral penicillin in reducing rheumatic fever, the condition which starts RHD. Benedict F Massell, an international expert on rheumatic heart disease from Harvard University, paid tribute to Burke in his 1997 textbook on the disease and highlighted that the treatment first advised by Burke had been shown to reduce the incidence of the disease from 13% to 1% in affected patients.

Seventy years later, Harrington and his colleague Dr Joe Gallagher in Gorey have taken up the mantle to become the source of transformative change in an effort to help save lives in Malawi using those same simple treatments.

Non- communicable diseases and injuries (NCDIs) account for one third of Malawi’s deaths and disabilities. Contracting NCDs such as RHD or chronic lung diseases including asthma, emphysema and chronic bronchitis means that sufferers are likely to face poverty as a result of lost livelihoods and high healthcare costs.

Non- communicable diseases and injuries (NCDIs) account for one third of Malawi’s deaths and disabilities. Contracting NCDs such as RHD or chronic lung diseases including asthma, emphysema and chronic bronchitis means that sufferers are likely to face poverty as a result of lost livelihoods and high healthcare costs.

The two doctors—in a partnership funded by the HSE through the ESTHER Ireland programme—are relentless in their charge to reverse the terrible effects of RHD on the people of Malawi, in part because of their interest in NCDs, but undoubtedly as a result of the devastation they have witnessed first-hand in the face of this tragically preventable disease.

“There are so many inequities associated with this disease. Healthcare systems had effectively deemed their work on RHD complete in the early part of this century only for the WHO to highlight that it remains a significant cause of death and disability in the poorest parts of the world, particularly for children and young adults with a mortality similar to HIV. It is a damning indictment that the drugs needed to treat this disease- penicillin in oral and depot injectable form – are so inexpensive. Yet so many continue to die from this condition.”

“There are so many inequities associated with this disease. Healthcare systems had effectively deemed their work on RHD complete in the early part of this century only for the WHO to highlight that it remains a significant cause of death and disability in the poorest parts of the world, particularly for children and young adults with a mortality similar to HIV. It is a damning indictment that the drugs needed to treat this disease- penicillin in oral and depot injectable form – are so inexpensive. Yet so many continue to die from this condition.”

The incidence of RHD, wherever it occurs within high, middle and low-income countries, is a marker for extreme poverty and social disadvantage. And latent RHD—meaning RHD with no symptoms—has a high prevalence throughout many low- and middle-income countries. Studies in Malawi have demonstrated that latent RHD in the country affects an estimated one in 35 children. The majority of RHD cases are detected only when symptoms of breathlessness have developed. At this point it is frequently too late to intervene, ultimately leading to debilitating heart failure and a high mortality rate with an average age at death of 28 years in a recent study.

So far, results from other work carried out by the Gorey-Malawi Health Partnership have been astounding. In 2018, St John’s Hospital in Malawi identified asthma-COPD as its NCD of choice and worked with Harrington and Gallagher to successfully implement an improved programme of treatment and prevention that reduced asthma-COPD admissions by 44%, and readmissions by 100%.

The implementation of a hypertension – cardiovascular health protocol at St John’s Hospital is now underway so that the project becomes more broadly based within the hospital and better aligns pharmacy supplies with hospital needs and develops sustainable clinical protocols and drug supply chains.

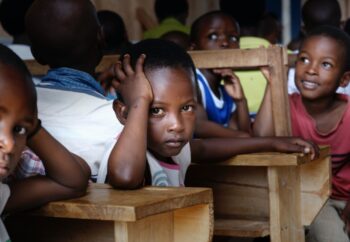

In 2019, the partnership took another leap: this time to commence work on improving community awareness of RHD at Chigwere, a remote rural location in the catchment area of St John’s Hospital. This project builds on the experience of the hospital in developing education for people with HIV in the Chigwere area of Northern Malawi and was supported by the charity RHD Action. It involves an education programme on sore throat, acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease to a core group of parents, teachers and community health workers.

Educational content is delivered in groups of no more than 30 people to ensure discussion and interest. In schools, students are supported in awareness raising around rheumatic fever or RHD and youth clubs help young people serve as ambassadors to raise awareness of this condition. Already patients are reporting a lack of awareness about the disease in hospitals that are not being reached by the partnership, so the objective is to also broaden that awareness at community-level.

The project now moves to help improve management of the condition with St John’s Hospital. A dedicated clinic is being established which will help diagnose the condition in its early stages. With support from the Dept of General Practice in the University of Limerick an ultrasound machine has been purchased which will allow identification of this condition as early as possible. Using mobile broadband, the images of the heart from this machine will be reviewed in real time in Ireland allowing clinicians in Ireland and Malawi to work together, improving diagnosis and management for RHD sufferers in the most rural of locations.

The Gorey-Malawi partnership represents a milestone in correcting the injustices of healthcare access for people living in developing countries, but also in furthering Ireland’s far-reaching influence and contribution in the field of RHD some 70 years after Dr Burke, then Medical Officer to the West Cork County Hospital, reported his findings on a cohort of 20 local patients.